This is the last of six posts I have written about the witch camps of Northern Ghana. You can find additional posts below.

“When will you file your story?” Cephus asks.

“Soon, it will happen soon.”

“It is about witches, right?”

“Yes, witches and wizards.”

“Where did you see wizards?”

“In Yendi.”

Cephus is the managing editor of The Mail, the newspaper I work for and he is calling me about the witch article, which has yet to be started. Â Not only have I yet to start it, but none of the notes have been transcribed. Â They are all scribbled in my tattered yellow notebook, which sits in the rucksack below my bed. Â The only thing I have looked at so far are the pictures.

It has been two weeks since I left Gambaga and I have spent most of the time on my balcony. Â It’s a private balcony, Â attached to my massive ocean-side room, all of which costs me about six dollars a night. Â My guesthouse is managed by a woman named Perpetual, but she is currently on vacation, so most of my interaction is with her sister Sawah.

Today Sawah is doing my laundry and I am watching intently from my balcony. Â The pools of flesh around her elbow flap as she scrubs my jeans. Â She wrings the soap from my underwear with the force of her palms. Â She hangs my light-blue dress shirts from the line with care and they bounce, ever so gently, as the wind whips past the beach, the palm trees and the stone gazebo in the yard.

Today, Sawah does my laundry. Â But most days, she spends her time sitting with a look of abject hopelessness on the stairs. Â The stairs face a wall. Â She could easily face the ocean, which bursts in torrents of white against the huge black rocks on the beach, but instead she faces the wall.

I try to write in the late afternoon, as the sun hemorrhages over the water in hues of purple and orange, but I can’t produce a word. Â I want to get a drink with Sawah and stare at the wall, but Sawah never drinks in public–she stumbles and slurs in public, but she only imbibes alone–so I go to the bar by myself, and then walk along the beach through the piles of litter that dot the sand. Â My thoughts begin to blur and pool. Â They run in jagged, uneven lines, like a glass of spilt water on a dirt floor. Â Mostly, I am awash in images– Polaroid pictures flipping through my brain.

I see Simon at dinner, eating voraciously, confiding his “secret” belief in the specious nature of the supernatural, licking the frothy head of a Guinness; the Gambaranna, cloaked in his flowing white tunic, staring ahead with his soft brown eyes, as I slip money under his rug; the Juju man, stonewalling me with his obstinate guru bullshit, mocking my questions in his tiny shack full of antiquated weaponry and voodoo charms; the guys at the bar laughing at the idea that witches may not exist; the youthful organizer, Ernest Cudjoe, telling me in his perfectly polished English, “It’s not up to me to decide who is a witch or not;” Magaji –the guilty witch–confessing spiritual murder listlessly with her dead gray eyes.

I see a copy of The Crucible in my hand in high school, a fantastical play about something that happened in America four hundred years ago and something that is happening in Africa right now. “Did you hear about the witch that flew into Nungua the other day on a broomstick without clothes on?” I recall a friend asking me. Â “RITUAL MURDER TAKES ANOTHER VICTIM,” a newspaper headline proclaims. “BOYS TURNED INTO SNAKES FOR BLOOD MONEY,” another shouts. Â I fixate on the dent in the forehead of the wizard in Yendi; the nail hole looms large in mind.

I want to write an op-ed, like I do in America whenever something offends me.  In America, I can call people out, I can  castigate them if I think they’re false or hypocritical, but in Africa my voice is so small.  I want to say that Northern Ghana is in the Stone Age and that these beliefs retard development, democracy and human rights, but my pulpit is so flimsy here. And who would ever feel sympathy for a witch?  And even those who might–like Simon–still don’t believe that maybe these men and women aren’t witches at all.

A deluge of pity hits me, followed by a breathless moment in which all I can hear is the mortar-like pounding of the waves. Â Pop, pop, bang, bang, bang, bang, bang, bang! The rocks take their beating peacefully. Â The tide crests, the sun fades, and a violent bout of loneliness descends upon me in its wake. Â It hurts more than usual this time.

Visit the Gambaga archive for all the posts in this series or check out the photo gallery for more images from the witch camps of North Ghana.

This is the fifth of six posts I’ll be writing about the witch camps of Northern Ghana. You can find additional posts below.

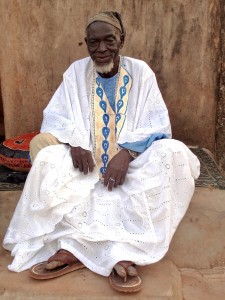

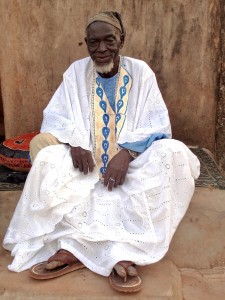

The chief of the Yendi camp alongside accused wizards

Simon picks me up at 5 am. It is not yet dawn but the moment preceding it, and I can feel the impending energy of the sun pressing violently against the black clouds. The motorcycle weaves jaggedly across the dirt road and past the prison, the canteen and the hot yellow Western Union that signifies the end of town. The sun punches through the clouds, flooding the plain with a soft, purplish glow. Men, women and children pour out of the bush and onto the road, proceeding toward town with baskets of goods on their heads.

Simon and I are going to Yendi, to visit Ghana’s biggest witch camp, which holds over seven-hundred individuals. The village was the site of a small war–more aptly described as a chieftaincy crisis–in 2003. The violence was the result of a long-lasting dispute between the Abudu and Andani tribes, which vie for power in the area. The conflict began when a mob stormed the palace of the sitting Ya-Na ( the regional chief), beheaded him and then killed another forty townspeople. In the aftermath, only a few of the perpetrators were brought to justice, and hostile tensions still hover in the area.

The witch camp in Yendi is not actually located in the town, but about forty kilometers outside of it. Before we begin the trek, we visit with members of Songtaba. a non-governmental organization (NGO) that advocates for those accused of witchcraft. The organization is coordinated by Enoch Cudjo. A college graduate with a degree in social work, Cudjo is young and brash. He wears a bright purple dashiki and, like others, is a bit nervous about talking to the press. However, after a few minutes of feeling me out, he expounds on his efforts to help those in witch camps.

What Songtaba primarily focuses on is integrating community members and “accused witches†together so they can live cohesively. Cudjo says that one strategy that has been particularly successful was building a well for a village inside of a witch camp, thereby forcing the townspeople to interact with the accused witches when they fetched water. As I had with Simon, I ask Cudjo whether or not he believes in the existence of witchcraft and/or that the women in the camp are witches. The question jars him, and he refuses to answer outright. “It is not up to me to decide who’s a witch and who isn’t,†he says. “Instead, I prefer to work on enhancing integration.â€

Simon and I depart and head toward the camp. As we grow closer, the road becomes increasingly bad and the landscape bleak. We stop for gas on the side of the road, where three teenagers have a small station where they sell liters of fuel contained in beer bottles. Two of them have chunks of scarred flesh surrounding their navels from poorly cut umbilical cords.

Finally, we enter the camp. The architecture is identical to Gambaga and the small, crude huts stretch as far as the eye can see. Simon finds the chief sitting under a tree. He is dressed in old dirty clothes and appears nowhere near as regal as the Gambaranna. I purchase a libation (a bottle of aperteshie) for a dollar as a gift, and the chief gives it a blessing before slugging down a glass. There is only one plastic cup to drink from so we pass it and the bottle around. Finally, it is my turn. I grimace and slurp down three ounces of the clear, potent moonshine, trying to minimize my shiver to the delight of the chief and his advisors.

The language spoken is too rare for even Simon to understand well. However, there is one young boy who speaks English and he is summoned to assist me in interviews. The chief says something to one of his assistants and two minutes later a half-dozen beaten looking wizards appear. They are covered in dirt and mud and two of them are wearing ski caps with crescent points at the top; oddly, they do look a bit like wizards

Previously I have conducted all my interviews one on one, but I decide that because there are six wizards, and I am half -drunk on moonshine, I will host a roundtable. I direct the wizards to all sit on one bench and they do, patiently awaiting my inquiries like Catholic schoolboys preparing for the confessional. I ask them why they were accused of sorcery. Madjuri, who has been at the camp for three years, says that he killed some young boys.

“Did you really kill them or were you just accused of killing them?†I ask.

“I killed them,†he said.

“Well, why did you kill them?â€

As the question is being translated, every one–the chief, the translator, the wizards and Simon–begins to laugh. I realize it’s a ridiculous question, but I don’t know what else to ask.

“He doesn’t know,†the translator responds. “He says he just did.â€

An accused wizard in Yendi who had a nail hammered into his head

The wizard on the far end of the bench catches my eye. He’s dressed in an oddly fashioned royal blue jacket; it looks like something that a sea captain might wear. He has a massive scowling face, and I notice a strange indentation on his head. He tells me that he was accused of witchcraft by two young boys who said they saw a vision of him in their sleep. He was beaten by a number of different men, approximately a dozen times. Then, one day they held him down and pounded a nail into his skull. The nail is still in his head and he can no longer see out of his left eye.

I take a dozen pictures of him, like he’s an animal at a zoo, and then give Simon the wave that means I’m finished. I toss my Yendi translator a weird psychedelic eagle t-shirt that was sitting in my bag–his shirt has more holes than cloth–and bump fists with the remaining wizards before leaping on the back of the motorcycle. We have to push it to get back to Tamale before dark, and I bob up and down as the bike plunges through rut after rut.

Back in Tamale, I pay Simon $40 for five days of work. It comes out to $2 per hour and it’s more than he’s made in the last month. We sleep in a terrible hotel–everything else is booked because of a convention–and I wake up in the morning to a cockroach sidling up my leg. I head to the bus station and two hours later I am riding on the big, comfy STC passenger bus back to Accra. I’m done with Gambaga. I sleep the whole way; I need it badly. I haven’t slept right in a week.

Visit the Gambaga archive for the first three posts in this series or check out the photo gallery for more images from the witch camps of North Ghana.

This is the fourth of six posts I’ll be writing about the Gambaga witch camps. Â You can find additional posts below

Magajia Dahamat Seidu

Magajia Dahamat Seidu is an admitted killer.  She murdered a child in her village of Zeongu almost twenty years ago.  She cursed it and  it died mysteriously.  She doesn’t know why she did it.  She just did.

At least that’s what an article from last year’s Daily Graphic tells me.  Simon shows me the article in his office when I ask if there are any witches who have confessed to witchcraft.  He saves all newspaper clippings that mention the camp.  I ask him if I can talk to Seidu.  A half-hour later, I’m sitting on a tiny footstool, chewing nuts and staring into her tiny wrinkled face and pooling brown eyes.

Seidu tells me, in short measured sentences, that, yes, she is a witch, and, yes, she did curse a child to death, and, no, she doesn’t know why.  “I just opened my mouth, and it spoke,†she says. The woman is not stable. She is unable to answer many of my questions, and it becomes apparent that Simon is filling in the gaps during translation.  I am a bit wary of her eyes–they are uncomfortably vacuous and constantly staring through me. I decide to cut it short after ten minutes.

“Done,†Simon says, surprised.

That night I have Simon and his wife, Evelyn, over for dinner.  I find a woman who will make me pasta and I order a six-pack of Guinness.  Simon shows up five minutes early in his best shirt, a faded Chelsea soccer jersey.  He drinks the beer with a disquieting fervor, not even waiting for the foam to recede.  Evelyn tells me that she has “small malaria†and asks if she can have some of my medication (I keep a prescription of malarone in my bag when I leave Accra).

I don’t eat any of my chicken, it tastes horrible, so they inhale it together, including the bones.  Suddenly I realize that I have spent the last three days looking for the answers to my questions about the Gambaga witch camp, when the best source was always sitting in front of me.  “You know, you must have one of the strangest job titles in the world,†I joke with Simon. “How did you ever become the manager of a witch camp? â€

Simon and Evelyn Ngote

Simon’s English is very good, although he has no formal education, and he unwinds a long, tightly constricted narrative about his past. He is from a small village, close to Gambaga, and has lived in the region most of his life.  He became involved in social work in the eighties, primarily assisting victims of river blindness, an insect-borne malady that affects the aged in rural areas.  One job led to another, and most were affiliated with the Presbyterian Church.  In 1994, he was offered his current position in Gambaga.

Simon cares more about the witches of Gambaga than anyone else I have met.  “I want them to live a decent life,†he tells me.  “I don’t think of them as witches but social outcasts.â€

“But, do you believe that they are truly witches?†I ask.

“My wife thinks I’m crazy,” he whispers, smiling at Evelyn, whose English is very poor, “but I don’t think all of the allegations are true.† He delivers the line as if he’s confessing an infidelity, a state-secret or a radical conspiracy theory.  The shocking thing is that in northern Ghana Simon’s belief–that witchcraft may not exist–is borderline sacrilege.  In fact, Simon tells me that if he attempted to debunk witchcraft in rural villages his efforts would not only be fruitless, but could damage him professionally.  “I would lose my credibility, people would think I was a crazy man,†he says.

Visit the Gambaga archive for the first three posts in this series or check out the photo gallery for more images from the witch camps of North Ghana.

This is the third of six posts I’m writing about the witch camps of Northern Ghana. Posts one and two are below.

Kambuna, a Gambaga juju man.

I am sitting in a shack in Northern Ghana across from a fetish priest. The rain pounds the tin roof in an eerie symphony; the water slips through the rafters and pelts my shoulders. There are a half-dozen voodoo dolls lying on the milk crate table in front of me.  A number of spears are mounted on the wall, along with a rifle, which looks old enough to be Davy Crockett’s. Regardless, it is hard for me to treat this situation with legitimacy for one reason. What sort of self-respecting fetish priest wears a Foster’s Beer shirt? If this man really had spiritual powers, wouldn’t he be sporting, at the very least, a Miller High Life tank top?

Simon brought me to meet the juju man, because he is one of the few individuals recognized as having supernatural powers that are used exclusively for good. The price to interview the juju man is three Cedi. This is triple the price to interview a witch, but I have interviewed seven witches over the last two days and their stories have begun to stagnate in my mind. I need another perspective and Kambuna, the Gambaranna’s spiritual adviser, is willing to chat.

According to Kambuna, he inherited his spiritual powers at the age of twenty-two from his father. Since then, he has been protecting the chief by entering the supernatural world in his dreams and locating any spirits that seek to do harm. Kambuna says that if he meets a malicious witch in the spiritual world, he “beats it down” spiritually. If that doesn’t work, then he will address the physical manifestation of the spirit (the flesh and blood witch) and give her a stern warning. He says such a warning will almost always achieve results. I want to know what else he sees in the spirit world, so I ask him.

He tells me that at night he holds court with a number of spiritual advisers that appear from across Ghana and the rest of the universe. They appear, not while he is sleeping, but while he is awake, in the form of tiny dwarfs. They are not visible to anyone besides him, and they advise him on what will happen in the future. He informs me that he has the power to transfer spiritual powers to others and that he has been teaching them to his son. The boy, about 14, is called in and enters nervously. I ask him if he has seen any dwarfs recently. He says he hasn’t.

Simon is taking the juju man in the Foster’s beer shirt very seriously, but there are moments when I feel like I’m on a hidden camera show. I want to show deference to local culture–to keep my mind as open as possible–but at the same time I want answers, sane answers, so I start to dig in. I ask Kambuna why his spiritual powers give him respect in the community, when the women accused of witchcraft are treated like criminals. He answers quickly, telling me: “They use their powers for bad, while I use my powers for good.” I ask him if he thinks that all the women in the camp are actually witches. “Of course they are, that’s why they are there,” he says.

Then, I ask what prevents the women from using their spiritual powers in the camp. He says that the power of the Gambaranna is so great that the women are rendered impotent. “Then why doesn’t the Gambaranna use his spiritual power to produce some food,” I ask.

He sidesteps me and says that the Gambaranna does plenty of things to help the women.  I ask the question again. Simon translates it and once again, I get a vague answer. I realize that regardless of how unimpressive he appears to me, this man holds an influential position in the Gambaga community. He is a top adviser to the most powerful man in the village and clearly won’t answer any question he doesn’t want to. If he was residing in Washington, D.C., instead of Africa, he might be Robert Gibbs.

I am frustrated and Kambuna appears to enjoy my irritation. Without prompting, he states that he can teach anyone supernatural powers who wants them. He asks me if I want them. Simon translates the question with such gravity that you would think he would have asked me if I wanted his kidney. “Of course, I want them,” I snap. Kambuna smiles a big, fat toothless grin, and rubs his fingers through his stringy goatee. Then, he mutters something to Simon.

“What did he say,” I jabber.

“He says that he doesn’t think you’re ready yet.”

Five minutes later, we leave. I feel completely inept as a journalist, like a softball pitcher who just had eight line drives nailed off his head. The mid-afternoon rain has cleared and Gambaga feels fresh and alive for the first time. Simon takes me to the canteen behind the prison where I munch on spaghetti beans and egg. It tastes bad, again.

Read the first post in this series or check out the photo gallery for more images from Gambaga

This is the second post in a six post series about the Gambaga witch camps in Northern Ghana.

The Gambaranna

The going rate to interview a witch is 1 Cedi (approximately $.67), so I make sure to fill my pockets with small bills before approaching the camp.  When I enter, I kneel and clap twice to pay tribute to the Gambarrana.  He is a Muslim and dressed in a long white flowing robe with blue trim.  He inquires of my purpose, and Simon translates to him that I am an American journalist working in Ghana and interested in writing about the witch camps.  Simon has told me the Gambarrana is skittish about providing access to journalists, as previously reporters have been critical of the conditions of the camp.  I assure him that I have heard many good things about his efforts and then supplement the statement by slipping 5 Cedi’s under his rug–as Simon had suggested.  He nods and we stroll inside.

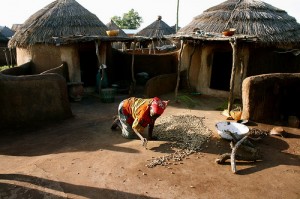

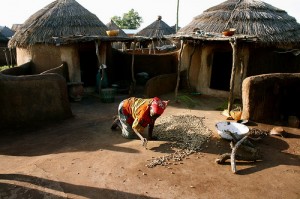

The compound is made  of a number of small, circular-shaped huts that face each other in groups of five or six.  They have dirt floors and no water or electricity.  When I arrive, the women have just returned from the field and are scattered about, mostly sitting on the ground or tiny footstools.  In the middle is a large pile of peanuts that they sift through, occasionally taking a handful to munch on.

An accused witch in Gambaga arranges nuts (photo by Brian McAndrew)

The women’s faces are weathered, their shoulders slumped, and they appear torn between two  forces: the survival impulse that drives them to push on and the anguish of their plight, which has caused them to be banished–under the threat of violence and even death–from their friends, families and homes.

The first interview I conduct is with Kondug Dute.  Approximately sixty years old, she arrived in Gambaga from her village ten years prior, after being accused of bewitching a child who had died.  Inexplicable deaths–especially among the young–are one of the most frequent motivators for allegations of witchcraft, and Dute was accused by the  son of a rival.  She was chased from the village amidst threats of violence and now lives in Gambaga selling firewood.  “I have been disgraced and separated from my family, yet I have done nothing,†Dute tells me.  Like most of the women I interview, Dute says that she is innocent of all allegations of witchcraft.  However, Dute and others do not deny that witchcraft exists.  When I ask one woman if she believes that her peers might be witches, she tells me flatly:  “There’s no way I can know that; it’s between them and God.â€

My first interview in Gambaga (Photo by Brian McAndrew)

I interview four women that evening and all of their stories are similar.  Most have been accused after a death in the village, others simply because a rival said they were “haunting them†in their dreams.

It is rare that there is any fact-finding effort in regard to the allegations facing an accused witch. The only possible vindication occurs during a trial by ordeal that is sometimes held at the witch camp.  In these cases, a woman slaughters a fowl in the presence of the Gambarrana and other spiritual leaders.  If the fowl dies with its wings facing upward, the woman is exonerated.  According to Simon, this happens on average 20% of the time, but even if a woman is found not guilty she will still often stay at Gambaga.  One woman, who had won her trial, tells me that the stigma associated with witchcraft is so great that she was unable to return to her home regardless of her “acquittal.â€

The women tell me that their biggest problems are a lack of food and basic healthcare.  They look emaciated and the few children milling about appear even worse.  One lays motionless on the ground the entire time I am conducting interviews.  It is naked and a horde of flies congregate around its buttocks.  For the initial twenty minutes, no one attends to it, despite the fact that it moans on and off.  I grow more and more disturbed by its presence and finally one of the women notices my discomfort and carries it to another part of the compound.  “It has a sickness in the rectum,†Simon says.

I pay the women and they thank me and insist that I take handfuls of peanuts.  It is just a bit after seven when I leave the compound, but there isn’t a single restaurant open anywhere.  I buy two packages of biscuits and head back to Martha’s. There I take a shower, pouring three buckets of cold water over my head.  I go out to look for a beer and find one and a few drinking partners as well.  I want to know if they believe that the women of Gambaga are actually witches, so after a drink I summon the nerve to ask them.

“Of course,†they say.  “Why else would they be here?â€

Read the first post in this series or check out pictures of Gambaga in the photo  gallery.

The following is the first of six posts I’ll be writing about the witch camps in Northern Ghana. Â Check back every other day for a new post.

An accused witch in Gambaga. (Photo By Brian McAndrew)

I arrive in Gambaga at dusk. The mosques are booming in evening prayer; their exaltations feel eerily clandestine in the murky twilight. The only illumination comes from a single halogen light above a beige sign for Martha’s Memorial Guesthouse. The beam spreads across the soft patch of mud below it like the fingers of an outstretched palm. At its tips sits a rectangle of solid white stone, and in that rectangle rests Martha, forever entombed in a heap of granite her husband purchased to memorialize her.

I arrange a room with Martha’s widower, a bespectacled pastor. There is no running water and there are faded blood stains on the sheets, but at $3.00 a night I don’t expect much. I have come to Gambaga–a small village in Ghana’s Northern Region–to follow up on a story I read in a local newspaper about “witch camps.†From the scant details in the paper, all I know is that Gambaga is one of many refugee camps for women who have been accused of witchcraft and exiled from their villages. The story is provocative enough that I decide to make the eight-hour trip to Gambaga on a whim.

When I awake the next morning, it is to a knock on my door from Simon Ngote, the manger of the witch camp. He had heard from the pastor that an American journalist was in town and assumed I was interested in the witches of Gambaga. Simon is in his late fifties–he has no recorded birth date–and tall and lanky with a grizzled salt and pepper beard. He and his family live in a modest-sized house on the outskirts of the village, which is provided by the Presbyterian Church as part of Simon’s compensation. However, a year ago, the church cut its funding to Gambaga–leaving him in penury. He continues to provide relief to the women in the camp, but has also assumed the role of unofficial tour guide in order to make ends meet.

Simon Ngote, Manager Gambaga Witch Camp

In his office, a cramped, lightless room adjacent to his home, Simon relays the basic layout and history of Gambaga to me. The camp was founded circa 1900 by an Imam named Baba, who felt pity for the women who were convicted of witchcraft, and at that time, often executed. It currently holds about eighty women; however there are six other camps in the region and their total population numbers over 1,000. According to Ngote, most of the women in the camp were accused of witchcraft in their village and then banished to Gambaga. There, they are overseen by a chief called the Gambarrana, who is supposedly able to subdue them through his spiritual prowess. The women are poverty-stricken and subsist on small earnings they generate from gathering nuts and firewood. I ask Simon if he can help me arrange interviews with some of them. “Sure, should I schedule wizards as well? he asks, dryly.

It is a strange proposition. We agree to meet that evening and I trail off back to the guesthouse, where I watch a gaggle of children play soccer in the grounds surrounding Martha’s tomb. The pastor sits in a plaid lawn chair facing the church. He doesn’t speak to me, but occasionally unveils a toothless smile.

For more images of the Gambaga witch camp, check out the photo gallery.